By Michel van Meersbergen, Holland

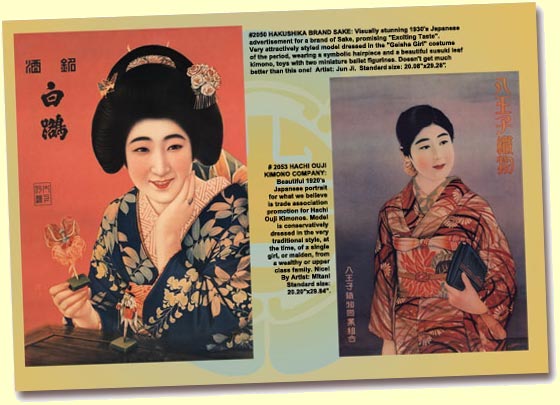

The word is out. A hipster Dutch marketing company stated Sake to be the hit of 2009. The coolest of all that’s hip – the anticipated replacement of the already three summer seasons lasting Proseco, which in my view is in most cases more sickening than the before hit: the rosé wines we saw throughout the before years. Should persons be concerned about quality and taste – the ones with focus on what’s in the glass instead of being focused on matching the colours of the wine and new sunglasses – as history tells us hypes and drop of quality or adjustments in taste to please the majority of consumers are always close of being hand-in-hand. Perhaps not. The Japanese seem to have a perfect understanding of what’s traditional and what’s not. That understanding might be a very important lesson to be learned by the Scots.

The word is out. A hipster Dutch marketing company stated Sake to be the hit of 2009. The coolest of all that’s hip – the anticipated replacement of the already three summer seasons lasting Proseco, which in my view is in most cases more sickening than the before hit: the rosé wines we saw throughout the before years. Should persons be concerned about quality and taste – the ones with focus on what’s in the glass instead of being focused on matching the colours of the wine and new sunglasses – as history tells us hypes and drop of quality or adjustments in taste to please the majority of consumers are always close of being hand-in-hand. Perhaps not. The Japanese seem to have a perfect understanding of what’s traditional and what’s not. That understanding might be a very important lesson to be learned by the Scots.

Sooo, Sake you say… Rice wine right? Not really. For the sake of understanding it’s better to call it a rice beer – without the hops that is. Not very unlike the mash used to distil spirit from. Further on we shall find out the destination ‘rice beer’ is completely wrong and establish Sake as an unique artisan product that can only be designated as: Sake… To put things in perspective lets have a little piece of history first. The origins of Sake are subject of debate but general agreement has it the first sake was brewed short after the introduction of wet rice cultivation in Japan, around the year 300 B.C. Predecessors of sake, the bare origins, go back even further to China in 4.000 B.C. yet the Japanese were the first to develop a method to mass produce the rice concoction we know as Sake these days.

Back then producing Sake was a communal activity were villagers would chew rice and nuts and spit the mixture in a tub. Next, clean water was poured on the mixture and it was left to ferment for an amount of time. This technique and the resulting liquid, called ‘Kuchikami no Sake’ or ‘Chewing the Mouth Sake’ was an important part in Shinto ceremonies and even in our modern times the ceremonial and social aspects of drinking Sake carries loud echoes from the past.

Take a large bowl…

To brew sake one needs rice, water, koji and yeast. Although producing Sake seems to look like a walk in the park it is in fact a highly refined process with endless variations – the scary part is the fact all these variations are well traceable on the palate – so the brewer must have a perfect clue what style of Sake has got to be brewed, this is where his experience comes in. Lets have a step by step look at the mentioned ingredients.

Rice (Sakamai)

In general 9 types of rice are used in today’s industry. Here is where the flavour profile begins as each type of rice brings its own distinctive flavour.

- Yamada Nishiki: The King of Sake rice. Fragrant and a well balanced soft style flavour.

This rice will be used for premium Sake. - Omachi: An original rice strain, much debate if this is the last ‘original strain’ in Japan.

Slightly timid on the nose but with more definition and earthiness on the palate. - Miyama Nishiki: Makes for a slightly sweet palate with more pronounced rice flavours, grip and a timid nose.

- Gohyakumangoku: Dry, smooth and clean with a refined nose.

- Oseto: Distinctive, rich and earthy.

- Hatta Nishiki: Timid nose, rich flavoured with a subtle earthyness.

- Tamazakae: Delicate and intense bringing complexity but difficult to brew with.

- Kame no O: Rich and full of flavour yet bringing some dryness as well as acidity. Not very much used.

- Dewa San San: Complex, off-dry and gentle on the nose.

(Besides these main types of rice, local varieties are used but quite rare. Mentioning them would fall outside the purpose of this epistle.)

Water (Meisui)

With over 80% water to be found in a bottle of Sake it’s understandable water plays a very, very important role. Even more so in the brewing process where the amount of water used exceeds 30 times the weight of the rice. Why is it so important? Lets start with the obvious, smell and taste. Take a sniff and sip of water from any tap in a major city and one will understand that ordinary tap water just won’t do another job than destroying the subtle taste and nose of Sake. It has to be pristine and pure – but not too pure!

With over 80% water to be found in a bottle of Sake it’s understandable water plays a very, very important role. Even more so in the brewing process where the amount of water used exceeds 30 times the weight of the rice. Why is it so important? Lets start with the obvious, smell and taste. Take a sniff and sip of water from any tap in a major city and one will understand that ordinary tap water just won’t do another job than destroying the subtle taste and nose of Sake. It has to be pristine and pure – but not too pure!

Already in the 1700’s the Sake few breweries were extremely in demand, all of them in the Hyogo prefecture. It has always been said it’s because of the water that the Sake coming from this region had, and still has, an outstanding quality. Before chemical analysis this was a given fact and when chemical analysis reached the desired level it was a proven fact. It led to a differentiation of types of water: Kosui (hard water), Nansui (soft water), Tsuyoi mizu (strong water) and Yowai mizu (weak water).

As with rice, these types of water have direct influences on how a Sake is brewed and so have an indirect influence on taste. One might think any well or spring water might be in the types of water mentioned so the question remains: what makes water good to brew with? Back to analysis.

Good water has:

a. a lack of iron, as it affects the colour of the Sake and becomes quite noticeable when Sake undergoes it short ageing.

b. a lack of manganese as it affects, under influence of ultraviolet light – as in direct sun light – the colour of Sake in a matter of hours.

c. a reasonable amount of potassium, magnesium and phosphoric acid. These compounds are of vital importance to enzymes and yeast of which more later.

Especially point c. makes a water ‘strong’ or ‘weak’. This refers to the way the fermentation is influenced by the water. In general ‘hard’ water is ‘strong’ water but remember that any of the types of water is a designator for quality. It all depends how the brewer interacts with the water and other ingredients. Having said that, some breweries use tap water, or even sea water that is altered to the likes of the brewer and despite loosing a lot of the romantic feel, one can produce a very good Sake with this ‘technical’ water.

Koji

Back to the olden days where the rise was chewed together with nuts before fermentation could start. The concept of adding enzymes was yet to be discovered, still it was precisely what the people did by chewing the rice. Koji took over that disgusting practice. Let’s have a look what Koji is. In essence it’s a mould. The mould is of a special kind called ‘Koji’ or ‘Aspergillus Oryzae’ and is cultivated on the rice grain. It’s job is to create enzymes that break the starch in rice into sugars and we know to well what yeast can do with sugars… The big difference between brewing beer (or mash) and Sake is most evident here. As barley generate enzymes by itself thru the malting process, rice has no chance of doing so (We return to this matter later). The enzymes have got to come from a different source. Here is where Koji come into town. When small batches of rice is steamed and sprinkled with Koji spores the mould developing on the rice will generate different kinds of enzymes of which some create glucose which will turn into alcohol eventually by yeast and some will create sugars that cannot be fermented but will have influence on mouth feel and flavour.

It’s clear Koji plays a major part in brewing Sake: no Koji means no Sake. No wonder lots of attention goes into producing Koji and every brewery will have its own slightly different way of coming up with Koji that is unique compared to another brewery. Here we have another ingredient that in the hands of a craftsman will bring a distinct flavour to Sake.

Yeast

The importance of yeast is well understood. Besides breaking up sugars into much desired alcohol, yeast brings flavour and character as well. Compared to the whisky industry, where the choice of a yeast strain seems only to relate to the amount of alcohol it can turn from the sugars, Sake is the garden of Eden for all that is yeasty. Already in 1900 the Central Brewers Union began archiving yeast strains from exceptional batches of Sake coming from large breweries and made them available to small(er) breweries. Besides the strains made available most of the breweries will have local strains (one brewery is rumoured to have over 1.000 different strains isolated) and some go as far by collecting natural strains of yeast from holy places – making for exceptional ceremonial Sakes that un doubtfully come at a price… Below an overview of the 15 most common yeast strains provided by the Central Brewery Union:

#1 No longer used – acidity too strong

#2 No longer used – acidity too strong

#3 No longer used – acidity too strong

#4 No longer used – acidity too strong

#5 No longer used – acidity too strong

#6 No longer used – acidity too strong

#7 Masumi. The most common used yeast giving a strong fermentation and a mellow nose.

#8 No longer used – acidity too strong

#9 Koro. Used in higher class Sakes giving good fermentation and a strong nose.

#10 Tohoku Moromi. Subtle grainy flavours with low acidity.

#11 No longer used – acidity too strong

#12 No longer used – acidity too strong

#13 No longer used – acidity too strong

#14 No official name but commonly known as Kanazawa Kobo and giving a fruity nose a low acidity.

#15 Akita Moromi (also know as AK-1) giving lots of refined character but is a bit difficult to handle as it’s sensitive to temperature.

Foamless versions or ‘Awa Nashi’ are available of #6, #7, #9 and #10 and are given the numbers #601, #701, #901 and #1001.

Foamless yeast have come in practice since it reduces heavily on labour costs – less cleaning of remnants of the foam and brings one third more capacity in the fermentation tanks. That space is otherwise reserved for the foam.

…and a large wooden spoon

Now that we know a bit about the ingredients, let’s have a look at the way they are put together; a look in the Kura (Brewery) and the brewing process itself. As written, it starts with proper sake rice.

– The first step is milling or polishing . Here a certain amount of the outside of the rice grain is removed. This is done to prevent a far to pronounced rice flavour in the end product. The polishing also is the main step in designating the grade of Sake that will end up in the bottle. (more about the grades of Sake later on). For a decent grade of Sake about 30% of the rive grain is removed, for the highest grade a minimum of 50% of the grain has to be removed, some top notch Sake goes to even 35% remaining of the original grain. Lots of care is taken about the level of polishing as removing too much can bring an enormous lost of flavour and character. Everything depends on the designated profile.

– The first step is milling or polishing . Here a certain amount of the outside of the rice grain is removed. This is done to prevent a far to pronounced rice flavour in the end product. The polishing also is the main step in designating the grade of Sake that will end up in the bottle. (more about the grades of Sake later on). For a decent grade of Sake about 30% of the rive grain is removed, for the highest grade a minimum of 50% of the grain has to be removed, some top notch Sake goes to even 35% remaining of the original grain. Lots of care is taken about the level of polishing as removing too much can bring an enormous lost of flavour and character. Everything depends on the designated profile.

– Next is washing and soaking the polished rice. The remnants of the polished rise, called Nuka, is washed away. The removing of this powder has quite some impact on the behaviour of the rice grain later in the brewing process, as Nuka affects the absorption abilities of the rice grain. This should be extremely consistent and even, Nuka prevents that. Sometimes Nuka is used to brew the absolute low level Sake, which I doubt is fit for consumption. After the Nuka is removes the rice is soaked, again a precise operation as each type of rice has a different optimum for the next step; steaming. Also the level of polishing is of great importance. High level polishing will end in ultra fast absorption of water. Where sometimes 12 hours of soaking will bring the optimum, in the last case it can be as little as a single minute.

– Now the rice is steamed. This is done in steaming vats (Koshiki) where steam comes from the bottom of the vat and works its way trough the rice. This technique brings a harder outside of the rice grain as well as a soft centre. When the rice is proper steamed the batch from the vat is dived. A part will be used to receive Koji, the other part goes straight to a fermentation vat.

– Koji Making. We could already read Koji generates enzymes that are needed to turn starch into sugars. Cooled steamed rice is sprinkled with Koji mould and taken to special climate rooms. Here it stays for 36 to 45 hours where it’s under constant surveillance. When it’s ready it will be used immediately in thefermentation process.

– Yeast starter. The plain steamed rice and finished Koji is mixed together with water and yeast.

This mixture is left to ferment for about two weeks.

– Mashing. The yeast starter is moves to a large tank where more rice, more Koji and water is added in three stages over a four day period. Over that period the volume of the original starter doubles and is left to further fermentation for about 18 to 32 days where the process followed closely for any needed adjustments to bring out the qualities needed.

– Pressing. When the mash, now called Moromi, is ready it needs to be pressed. With the pressing less and unfermented solids are removed. This can be done by machine yet the old way of putting the Moromi in canvas bag which are squeezed by weight (drip-pressed) or hand is highly praised.

– Filtration. The pressed Moromi, already called Sake is left for a few days where more solids settle out and run through a charcoal filter.

Here flavour and colour can also be adjusted. Every brewery has its own degree of filtering depending of house style or profile wanted.

– Pasteurisation. The filtered sake is now pasteurised once by streaming it into a pipe that is immersed in hot water.

This process will kill any bacteria and deactivate enzymes that could otherwise affect flavour and colour once the sake is bottled.

– Ageing. After pasteurisation the Sake is left to age for about six months. This is done in large tanks, sometimes in large glass vessels but the ageing is important to round out the flavour. Just before bottling, where the Sake holds about 20% alcohol it’s watered down to about 16 % and batches are vatted to ensure consistency. Also a second pasteurisation could take place.

All Sake is equal but some are more equal…

Let’s make things more complex. The endless variations of ingredients and brewing is certainly not the last stop.

Sake exists in various grades. These grades are not discriminating about quality per se but tell us a lot about certain factors in the brewing process. Having said that, the highest grade is usually of the highest quality, yet a lower grade might bring the same drinking experience or enjoyment, so don’t get carried away by the grades!

Sake knows three main grades which fall apart in two main divisions: With or without added alcohol.

‘What? Added alcohol??’ I can hear you say. Well yes. Just after World War 2 when rice was in very short supply breweries were allowed to add some pure rice alcohol to sake to boost up the ABV. The results of this practise were very encouraging so the practise remains to this very day. This style makes for wonderful fragrant Sake, a more lighter style that would suit springtime and summer evenings very, very well. In my opinion adding alcohol – integrity counts here! – is of no negative influence to quality! Let’s have a look at the grades starting with the premium levels with no added alcohol ranging down to up.

– Junmai-shu

Jumai is made only with rice, water, Koji mould and yeast. The rice must be polished to at least 70% of the original grain.

A subclass of Junmai, called Tokubetsu Junmai, is made with a higher quality rice with a higher level of polishing.

– Junmain Ginjo-shu

Here the machineries step aside for more traditional methods and tools. The rice must be polished to at least 60% of the original grain and fermentation happens a colder temperatures for a longer period of time which results in Sake that is generally lighter, fruitier and more refined than a Sake from the Junmai grade.

– Junmai Daiginjo-shu

Considered a subclass of Junmai Ginjo. Sakes from this class are the crown jewels of the breweries. Using the best ingredients available and very labour intensive methods. The rice must be polished to at least 50% of the original grain. Usually these Sakes are light, complex and have a nose to die for.

The premium level grades with added alcohol ranging down to up.

– Honjozo-shu

Honjozo is made only with rice, water, Koji mould, yeast and a small amount of pure distilled alcohol (Brewers Alcohol). The rice must be polished to at least 70% of the original grain. These Sakes are mild and very easy to drink. A subclass of Junmai, called Tokubetsu Honjozo, is made with a higher quality rice with a higher level of polishing.

– Ginjo-shu

The same quality as Jumai Ginjo. These Sakes are perhaps more aromatic compared to the ‘without’ versions in the same grade.

– Junmai Daiginjo-shu

The same quality as Junmai Daiginjo. The best a brewery can produce.

One should keep in mind that these grades are arbitrary. The levels of rice polishing are the minimal level so a brewery might produce a Junmai with rice that has a polishing level of 50% – making it a possible Junmai Daiginjo – but won’t grade it as such. There are many reasons for doing so, it’s down to brewery policy. To stir things up some more there are more grades and types. Lowest grade is called Futsuu-shu. This is Sake that will not meet minimal requirements to get into the Junmai or Honjozo grade. It is safe to say that with Futsuu-shu grade Sake we’re well into blended country when sake is compared to whisky. Taking this compartion a bit further, some blends are quite well drinkable and will at least bring enjoyment. The same goes for Sake from the Futsuu-shu grade. Besides the three premium grades and the bulk grade of Futsuu some other types of Sake are available (these types can be in any of the above grades):

– Nigori-sake

This sake is cloudy or milky in appearance. It’s not fully pressed to keep some unfermented rice particles.

This generally makes for a sweet and creamy texture but sometimes it can be chunky and chewy.

– Yamahai-shikomi & Kimoto

Two types with variations in the brewing process. The yeast starter is made differently in the way that yeast is allowed to be more ‘violent’ and some bacteria is allowed to be present. This make for a Sake that is said to be ‘gamier and wilder’.

– Nama-sake

As we could read, the majority as Sake is pasteurised twice; after aging and just before bottling. Nama-sake is a type of Sake that pasteurised once or not at all. It brings a more fresh and zingy note to Sake. There are three sub-types:

1. Nama zume: Sake that is pasteurised after aging.

2. Nama chozo: Sake that is pasteurised just before bottling.

3. Hon nama: Sake that is not pasteurised at all.

– Koshu Sake

Koshu Sake is aged Sake. The Sake is kept in large glass containers for a period of time. This can be from one to sometimes ten years.

Sake that age has an almost dark brown colour. Adding to complexity but loosing much of the freshness, Sake of this type comes at a price; only the highest grades of Sake will be used.

The fiddly bits, stoneware or glassware?

The general perception of drinking Sake is this: warmed from a small stoneware cup and when it’s really fancy a small wooden container with a pinch of salt on the edge. This is about the same as drinking Single Malt Whisky from large tumblers with ice cubes and soda water added.

The general perception of drinking Sake is this: warmed from a small stoneware cup and when it’s really fancy a small wooden container with a pinch of salt on the edge. This is about the same as drinking Single Malt Whisky from large tumblers with ice cubes and soda water added.

Only the lower grades of Sake are drunk warmed, although some Junmai grades as well – let’s forget about those as they are scarcely seen. The main reason to warm it is to get rid of any sharp components in the Sake, not unlike drinking blended whiskies with added ice to get rid of certain off-notes or an overly grainy character. The wooden container is also used for the lowest of low, where the wood itself acts as a mask for the off-notes. The reason for the pinch of salt on the edge should be clear by now. By no means I would force people to drink their Sake otherwise but I do question the quality of Sake that has to be drunk that way. There’s nothing wrong with warmed Sake we see normally in the restaurants. The Futsuu-shu grade is made for enjoyment and warming it will take round out the sometimes excessive added alcohol. The small stoneware cups can have a lovely appearance and may add to the exotic feel in a Japanese restaurant. As long as no-one pours his own cup, this should always be done by someone else, one shows a basic knowledge of Japanese etiquette.

Premium grade Sake is best served cooled and from a wine glass. The degree of cooling varies. Some are at the top around 50C, some at 100C while some others just below room temperature. It’s a matter of trail and error. Best to take a bottle and have a glass straight from the fridge and try it several times over a period of a hour or so. At a stage you will feel the Sake comes together and showing all facets it has – this will be the right temperature. A medium large wine glass will bring out all nuances in nose, mouth feel and taste. The Austrian glass company Riedel has two designated Sake glasses: ‘Daiginjo’ from the ‘Vinum’ series and the stemless ‘414/22’ from the ‘O’ series. I compared both glasses with several other glasses (also from Riedel) and I have to say, they work very well. A small investment in decent and dedicated really pays off.

Looking back and forth

I hope you remind one of the opening lines of this e-pistle; where quantity is in demand, quality might suffer. With Sake about to boom big time in Europe, does Sake have a future? Here is where Japanese tradition jumps onto the band wagon. As one can understand easily, with all the variable ingredients and possible profiles coming from them is isn’t too hard for breweries to catch up with demand. For a year or two demand for a lighter style of Sake arose, most breweries responded to that question. And doing this without affection their more traditional product. The same goes for label and bottle design. In my opinion it is here where the Japanese Breweries shine: one brewery can carry various brands in various grades. Each the result of their own unique ingredients and brewing techniques and covering much of the spectrum from cheap to very expensive. Try to compare this with lots of beer breweries and you know what I mean. In a way I’m thinking if this way of managing a product might be something the Scots should look into. The ‘upgrading’ of many SMW’s, with a renewed costumer in mind – demanding ‘classy’ bottle design, ditto labels, a more neutral taste etc. etc. – all resulting in much more serious upgrades on the financial side . I doubt if the general ‘young and concerning’ costumer is more sensitive to tradition or to a well crafted campaign that is tailored to their (supposed) likings. In a way a traditional product doesn’t have to be positioned in a traditional surrounding per sé.

Recommended reading and Kampai!

Looking for more information? Please turn to the website of John Gauntler (www.sakeworld.com) Everything Sake is mentioned on his site like the Sake meter (an e-pistle on itself), well written and larded with tips and tricks, as well as a good buying guide: what brands to have or to avoid. Better still, sign up for his newsletter! For the Dutch readers the site of Mr. Sake Europe and Beyond, Simon Hofstra, is worth a visit – he boosts a very nice collection (wholesale only) but is always willing to provide addresses where to get the nectar. The site of the Japan Prestige Sake Association lthough in Japanese will help you identifying some labels and brewery names.

Kampai!