By Lex Kraaijeveld, UK

A few months ago, a wee piece in the British newspaper The Independent caught my eye: “Whisky Magazine discovered in Antarctica!” it said. No, this was not Marcin Miller celebrating the first Antarctic subscription to Whisky Magazine, but a discovery by polar historian David Harrowfield which adds a fascinating little twist to whisky history. The ‘whisky magazine’ in question is titled Dawson’s Annual 1910 Review of Reviews. It contained advertisements of distributors of Peter Dawson’s Old Scotch Whisky from around the world while part of the magazine contained pages with dates, which could be used for diary notes. So how did this piece of whisky advertising end up in Antarctica?

A few months ago, a wee piece in the British newspaper The Independent caught my eye: “Whisky Magazine discovered in Antarctica!” it said. No, this was not Marcin Miller celebrating the first Antarctic subscription to Whisky Magazine, but a discovery by polar historian David Harrowfield which adds a fascinating little twist to whisky history. The ‘whisky magazine’ in question is titled Dawson’s Annual 1910 Review of Reviews. It contained advertisements of distributors of Peter Dawson’s Old Scotch Whisky from around the world while part of the magazine contained pages with dates, which could be used for diary notes. So how did this piece of whisky advertising end up in Antarctica?

In November 1910, the British Antarctic Expedition, led by Robert Falcon Scott, left New Zealand with the main aim of being the first to reach the South Pole. Many books and documentaries have told the story of how Scott and four companions (Evans, Oates, Wilson and Bowers) reached the South Pole, only to find that the Norwegian expedition led by Amundsen had beaten them by a month. The tale of them perishing on their way back is among the most poignant of polar exploration. What is less well-known is that, besides reaching the South Pole, the expedition also had clear scientific aims and that a group of six people, called the ‘Northern Party’, was sent out by Scott separate from the ‘Pole Party’ to explore an unknown area of Antarctica. The whisky magazine is linked to this ‘Northern Party’. It had been used by a member of the party as a diary during their stay in Borchgrevink’s hut at Cape Adare and, obviously, left behind. It was found, covered by decades of penguin guano, and removed by David Harrowfield in January 1982 from a depot established by the ‘Northern Party’ on top of Cape Adare in late December 1911.

The magazine was put in the hut and returned to New Zealand for conservation in 1990. The party appears to have had several copies of the magazine: Raymond Priestley, one of the members of the party, writes in Antarctic Adventure, his account of the expedition: “… we had with us two copies of the Review of Reviews, and these were read from cover to cover, advertisements and all.” Conservation of the brittle pages was undertaken by Lynn Campbell, Robert McDougall and Kirsten Elliot. Analysis of the script is under way to ascertain which of the people in this party (besides Priestley, the party included Campbell, Dickason, Browning, Abbott and Levick), is the author of the diary. At the moment, it actually looks as if the diary is in more than one hand.

The magazine was put in the hut and returned to New Zealand for conservation in 1990. The party appears to have had several copies of the magazine: Raymond Priestley, one of the members of the party, writes in Antarctic Adventure, his account of the expedition: “… we had with us two copies of the Review of Reviews, and these were read from cover to cover, advertisements and all.” Conservation of the brittle pages was undertaken by Lynn Campbell, Robert McDougall and Kirsten Elliot. Analysis of the script is under way to ascertain which of the people in this party (besides Priestley, the party included Campbell, Dickason, Browning, Abbott and Levick), is the author of the diary. At the moment, it actually looks as if the diary is in more than one hand.

But why would a magazine with whisky advertisements be present in a polar expedition in the first place? First of all, Scott’s expedition did bring whisky along to Antarctica. Six cases of whisky (or possibly five; the records are a bit contradictory) were supplied to the expedition by Peter Dawson Ltd, which explains the presence of the magazine. And whisky was not the only alcoholic drink they brought with them. On board of the Terra Nova, the ship that brought them from New Zealand to Antarctica, Christmas was celebrated with champagne, port, liqueur, beer and whisky.

On sledge journeys over the ice weight is crucially important and there is obviously no place for luxuries; nevertheless brandy was taken along for ‘medical comforts’ and a bottle of brandy was also left at one of the depots laid down for the return journey from the pole. And humans weren’t the only potential recipients of some medical spirit. A photo taken by Herbert Ponting shows whisky being poured down the throat of a pony that went for an involuntary swim in the icy Antarctic water during the unloading of the Terra Nova.

Scott’s expedition was certainly not unusual in taking along alcoholic beverages. Many, if not all, of the famous polar explorers around the turn of the 19th/20th century brought alcoholic drinks with them, always either for special occasions or for medical emergencies. Christian Borchgrevink brought along whisky, cognac and port. Ernest Shackleton mentions wine, beer, champagne, crème de menthe, whisky and brandy (one of his unlucky ponies received half a bottle of brandy to warm up). Roald Amundsen talks about Lysholmer schnapps, aquavit and gin. At the opposite end of the world, Fridtjof Nansen had Ringnes bock-beer and Linie aquavit with him, members of the D’Abruzzi expedition celebrated with cognac when they reached a point further north than Nansen, and Robert Peary (who may or may not have been the first to reach the North Pole) repeatedly mentions brandy as part of the sledge supplies. Interestingly, Frederick Cook (who may or may not have reached the North Pole before Peary) does not mention any alcoholic drink; of course absence of proof is not proof of absence.

A rather unusual spirit came into being during the Scottish National Antarctic expedition in 1902-04. A barrel of porter, supplied by Guinness, started freezing and it appears that, as a result of drinking the remaining unfrozen (and highly alcoholic) liquid, matters got a bit out of hand. Quite possibly, this ‘freeze-distilled whisky’ is the only spirit actually distilled (though involuntarily) on Antarctica ….. it shares being a true polar spirit with a ‘whisky’ freeze-distilled in barrels of beer during the overwintering of a group of Dutch sailors on Nova Zembla, an island off the north coast of Siberia, in 1596.

A rather unusual spirit came into being during the Scottish National Antarctic expedition in 1902-04. A barrel of porter, supplied by Guinness, started freezing and it appears that, as a result of drinking the remaining unfrozen (and highly alcoholic) liquid, matters got a bit out of hand. Quite possibly, this ‘freeze-distilled whisky’ is the only spirit actually distilled (though involuntarily) on Antarctica ….. it shares being a true polar spirit with a ‘whisky’ freeze-distilled in barrels of beer during the overwintering of a group of Dutch sailors on Nova Zembla, an island off the north coast of Siberia, in 1596.

The link between whisky and the poles reaches into the present. On June 2 2002, Ann Daniels and Caroline Hamilton arrived at the North Pole, making them the first women to walk to both poles (they reached the South Pole, as part of a 5-woman team, in January 2000). They celebrated their achievement with a miniature bottle of whisky.

And as I was working on the final version of this article, an obituary appeared in The Independent of the explorer Charlie Burton. On Easter Day 1982, he and Ranulph Fiennes became the first men to reach both poles by surface travel. The photo accompanying the obituary shows Charlie Burton at the North Pole, with a grin on his ice-covered face and a bottle of Jack Daniel’s in his hand …..

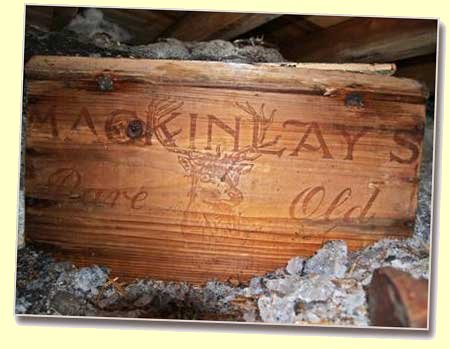

The article above was published in Celtic Spirit in 2002. But earlier this year a very interesting whisky find was reported from Antarctica and this find warrants an update. Two cases of MacKinlay’s whisky were excavated from the ice beneath Shackleton’s hut. MacKinlay’s was the official whisky supplier to Shackleton’s expedition and as such they provided 12 cases of their blended whisky. Some empty bottles had already been found, but these cases contained the first full bottles of whisky discovered on Antarctica. According to a certain Charlie Maclean, the whisky should still be perfectly drinkable …..

I could never have written this article without the kind help of David Harrowfield and Fiona Wills of the Antarctic Heritage Trust and I owe David, Fiona and the Trust my thanks for the permission to publish a few of the diary pages and the photo of one of the two cases of MacKinlay’s whisky. The AHT, a New Zealand based charity, has recently launched a £10M international heritage restoration project to restore the historic huts of Scott, Shackleton and Borchgrevink in the Ross Sea region of Antarctica and is appealing for financial help to safeguard this British heritage. For more information visit their website www.heritage-antarctica.org.

The photo of the pony (‘Giving whiskey to a pony which swam ashore’), taken by Herbert Ponting on February 3 1911, comes from the Pennell Collection at the Canterbury Museum (ref 1975.289.2); my thanks to the Canterbury Museum for the permission to use the photo in this article and to Christine Whybrew for her help in obtaining the photo. Permission of the Canterbury Museum must be obtained before any re-use of this image.