By Krishna Nukala, India

Whisky, I know for sure, is a subject that is of growing interest to many an Indian palate. Naturally it excites me to write on this topic because I have a little to share from my experiences with this noble drink. The fact that real whisky’s ingredients are barley (although other grains are permitted too), water, yeast and most importantly time, are now known to all.

Whisky, I know for sure, is a subject that is of growing interest to many an Indian palate. Naturally it excites me to write on this topic because I have a little to share from my experiences with this noble drink. The fact that real whisky’s ingredients are barley (although other grains are permitted too), water, yeast and most importantly time, are now known to all.

But appreciating whisky is a different ball game and is an outcome of acquired taste. And when it comes to Single Malts, the grammar of whiskies, the taster (or should I say the connoisseur) has acquired his taste painstakingly over a long period of time. For an Indian palate this process is even more difficult, as the stuff is sui generis to Celts and most of the smells and tastes that are described in Single Malts are from the dietary menu of the western world.

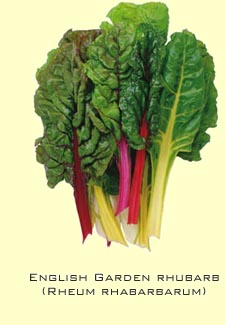

For example smells and tastes in things like rhubarb, licorice, short bread, marshmallows, junipers, thyme, rosemary, etc are unknown to general Indian palate although some western tastes like those found in prunes, plum cake, strawberries, garlic bread, etc are now familiar to many Indians. I am mentioning this because these are some of the flavours and tastes that one often encounters while “nosing” and “tasting” Single Malts.

On the other hand, when I detect our own Indian smells & tastes like asafetida (*), ripe guava (*), betel nut (*) or even green chillies in some of the Single Malts, my fellow drammers look at me with blank faces! That brings me to a discussion- what should an appreciative Indian taster like to find in his whisky? Well – definitely not soda, water and ice.

Even today Indians continue to consume large tumblers of water and soda laced with whisky.

Inferior whisky producers, since time immemorial have led us to believe that the only way to withstand their nascent produce is to add lots of ice, water, soda or even cola. As a result, the general Indian palate has not understood how to appreciate a decent dram of naked whisky. The aim seems to have a ‘good kick’ out of the stuff, no matter what it is and when you try to reason out with “What you drink is also important”, you often lose the debate when the guy counters, “Who cares about the taste? I am not a snob.” However, I am happy to find today that there is an increasing tribe of those who are now fed up with what they have been drinking and are asking for quality. Thankfully for this tribe, bless their souls, you do find now in India, some good blended whiskies and some imported standard OB malts. While the connoisseurs, I am sure, continue to source their quota during their sojourns abroad or courtesy- friends and relatives during their home comings. Imported Scotch is still out of reach of general Indian public and the government is ensuring the status by maintaining outrageously high levels of duties and taxes. This is a different topic by itself and one can write volumes on it.

What are the tastes that appeal to the Indian palate and which are the whiskies that offer these tastes?

I can safely vouch that the Speyside will be their first choice followed by Highlands stuff. The Indian palate is robust, as it has been subjected to lots of spices since its infancy and I am afraid, the lowland whiskies would be a tad too light for them. And Islay whiskies? I think it would be the same as with any one who has just been initiated into the world of whiskies. Either you love them or hate them.

Indians would love those heavily sherried Speyside whiskies.

I mean whiskies from distilleries like Glenfarclas, Benrinnes, Macallan, Aberlour, Glenrothes, Tomintoul and even Cardhu.

The sweet and honeyed tastes accompanied by spices like cloves, nutmeg and cinnamon would easily be recognised and appreciated. The tannins in the whiskies with thick mouth feel, is like chewing betel nuts, which incidentally is India’s hereditary pastime. And if you have had a drink too many, the dark coating on the tongue is similar to the reddish stains of ‘paan‘ (betel leaves, betel nuts with calcium hydroxide) which is a bonus. This is where the sherry finished whiskies score over their counterpart, bourbon finished whiskies. Having initiated into this, the Indian palate can upgrade itself to spicier and adventurous Highland stuff like Dalwhinnie, Dalmore, Clynelish, Glenmorangie or even Highland Park. One of the whiskies I can swear that would be a great hit in India is Glengoyne. The Indians would LOVE it.

Among the other whiskies the Indians would dare to try after initiation would be Lagavulin and Port Ellen.

As already mentioned before, due to high tariffs, Single Malts are not generally available, although I am told that Diageo and Allied Domecq have now established offices in India to cater to (or capture?) a niche segment. Single Malts are now available in all 5-star hotels and some high-end bars in Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore and Hyderabad. You can have a dram of standard Glenlivet 12yo (43%, OB) at Rs.700, i.e. EU 11.66 – and I am sure those enjoying would be doing so at their corporate expenses.

One of the latest developments in India is the evolution of Single Malt clubs and I happen to know a few esteemed members personally. One is Suresh Hinduja who maintains a food and drinks website called www.gourmetindia.com and the website has a colourful forum where whisky is discussed passionately. Abhinav Aggarwal from Mumbai, another passionate member, has not yet developed his blog but is joined by another malt enthusiast Keshav Prakash, a cinematographer (who happens to be a friend of Rob Draper).

Yet another worthy name to mention is Vikram Chanty, CEO of www.tulleeho.com – India’s premium website on alcoholic beverages. Except for selling alcohol, it features everything on drinks. During last week’s sojourn to India, Charles Maclean, our undisputed guru, was mentioning to me that he came across a few enthusiasts in Delhi who are part of a Single Malt club. The interest in SMSW is growing exponentially in India and if the tariffs are brought down to local excise duty levels by the government, I am sure the Scotch Whisky Industry would have a daunting task to meet the world’s demand.