By Lex Kraaijeveld, UK

Several whisky books state that Lomond stills produce a much oilier whisky than traditional stills. A few quotes as examples:

Several whisky books state that Lomond stills produce a much oilier whisky than traditional stills. A few quotes as examples:

“… variant of the pot still, which makes it possible to produce stronger, oilier whiskies.”

“… producing a comparatively heavy and oily whisky.”

” … thus giving a heavier oilier result.”

OK, you might say, what’s the problem with that? Well, if you consider what the underlying idea was for designing Lomond stills, it is a bit strange: Lomond stills were designed to allow the distillation of a wider variety of whiskies in the same still, not to produce

an oilier spirit.

The Lomond still was developed in 1955 by Alistair Cunningham, a chemical engineer with Hiram Walker, in cooperation with Arthur Warren, the company’s draftsman. Their brief was to find a way to increase the variety in the company’s whiskies to meet demand from blenders.

After experimenting with mashing time, fermentation parameters and the length of the spirit run, the solution proposed by Cunningham was to change the shape and working of the still. On top of a pot, this new still type had a short column with straight sides. Inside the column were three plates which could be turned from horizontal to vertical to allow variation in the amount of reflux. The plates could also be water -cooled or left dry, which allowed for more control of the reflux. In addition to the plates, the angle of the lyne arm could also be changes from pointing up to pointing down. Again, this allowed for even more control of the reflux and therefore of how ‘heavy’ the whisky would be. Incidentally, my attempts to get a diagram of the inside of a Lomond still all met with ‘this is confidential information’ replies.

Made in Govan, the first half-size Lomond still was installed at Hiram Walker’s Dumbarton complex in 1956. It was soon replaced with a full-size still when the half-size model was taken to Glenburgie and subsequently to Scapa. At the Dumbarton complex, the Lomond still was used as a spirit still in tandem with Inverleven’s wash still. The whisky running of the Lomond still was simply called ‘Lomond’. The rectifier plates were later removed because Lomond was too different from Inverleven.

Several other distilleries owned by Hiram Walker were fitted with Lomond stills. At Glenburgie distillery, a pair of full-size Lomond stills was installed in 1958. The whisky from these stills was named ‘Glencraig’ after Willie Craig, the company’s production director. Miltonduff distillery got a pair of Lomond stills in 1964. The whisky from this set of stills was called ‘Mosstowie’. By 1981, production of Glencraig and Mosstowie had ceased because of two reasons. First of all, the experiment didn’t work as well as expected in the long run. Over time, the plates became covered in residue, which was difficult to clean. Also, there was more demand for Glenburgie and Miltonduff, so space and resources were needed for expansion in that direction. The Glencraig stills were removed and the Mosstowie stills were cannibalized for building a new set of traditional stills. The Lomond still at Inverleven was mothballed in 1985.

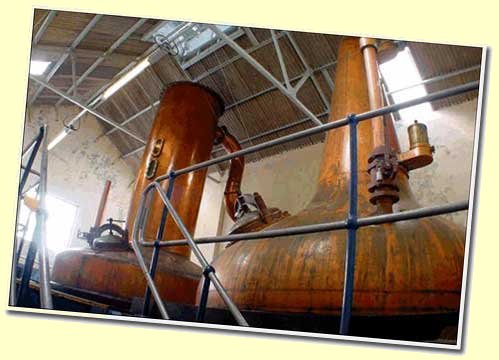

The only place where a Lomond still is still working today is on Orkney. Scapa’s wash still (on the left in the picture above) is a Lomond still, although the rectifier plates have been removed and a purifier has been added to the side of the still. The original Lomond still at Scapa is said to have been installed with rebuilding work in 1959; the present Lomond still seems to date from 1971, but solid confirmation of these details appeared hard to get.

People can wax lyrically about the beauty of traditional pot stills, but Lomond stills have never inspired much poetry. Tom Morton, in his book Spirit of Adventure, describes them as “indisputedly ugly”: “oversized upside-down dustbin made of copper, or the expanded head of Dorothy’s Tin Man”. Although Lomond stills surely were not designed to produce an oilier spirit, the idea seems to be pretty well established in at least parts of the current whisky literature. So are whiskies from Lomond stills really more oily? The only way to test this properly would be to have a single batch of wash split in two, one half distilled in Lomond stills, the other half in traditional stills, mature the spirit in the same type of casks, for the same length of time, in the same place, and then compare them in a side-by-side tasting. That’s impossible to achieve with available bottlings, so the next best thing is to conduct a number of comparative tastings and see whether some sort of consensus emerges.

Lomond single malt is only bottled twice, in 1992, by the Scotch Malt Whisky Society. These bottles have long sold out, so I was not able to compare Lomond with Inverleven myself. Nor was I able to get my hands on notes of a comparative tasting of Inverleven and Lomond. Still, given how rare a whisky Lomond is, it is interesting to have a look at the SMWS’s official tasting notes for distillery number 98:

Lomond 20yo 1972 (58.3%, cask 98.1)

Pale gold in colour, from a plain oak cask. A sharp, light nose which does not alter noticeably with water. Neither peat nor sherry on the nose, though a slight fruitiness, as of peaches. Sweet to start, it is salt to finish, with lots of tannin, from the oak.

Lomond 19yo 1973 (60.6%, cask 98.2)

Slightly darker in colour than its predecessor, but with the same sharp nose. This one, however, dulcifies with water to yield camphor and a bit of Hessian from the bungcloth. There is a taste of sharp fruit: dried apricots or pears and a very dry, lingering aftertaste. A clean, uncomplicated whisky. Someone said not a headache in a gallon, but members are advised not to take this on trust.

Not a single mention of the word ‘oil’ …..

Of course people differ in how they experience taste, but the supposedly ‘oily’ character of Lomond still whiskies is not so much a matter of taste, but more of mouthfeel, of body, and therefore less likely to vary between people. The Belgian whisky club Slainté recently organised a tasting where, in two trios, they compared Lomond still whiskies with their sister whiskies from traditional pot stills. The first trio consisted of a 16yo Glenburgie bottled by Cadenhead, a 13yo Glenburgie bottled by Gordon & MacPhail and a 20yo Glencraig bottled by Cadenhead’s; all three whiskies were bottled at cask strength. Here’s a summary of their notes on palate and finish:

Glenburgie 16yo 1985 (Cadenhead’s) – aggressive, smoky, spicy, almond-vanilla-caramel, sweet fruity

Glenburgie 13yo 1990 (Gordon & MacPhail) – soft, round, oily, dark chocolate, raisins, fruit cake, sherry, smoky

Glencraig 20yo 1981 (Cadenhead’s) -fruity, sweet, vanilla, nuts, peaty, buttery

The second trio was made up by two 12yo bottlings of Miltonduff (one recent, one from the 1980s; both at 40-43%) and a 29yo Mosstowie bottled by Cadenhead’s (at cask strength). Again, some of their notes on palate and finish:

Miltonduff 12yo (recent bottling) – light smoke, malty, wet grass

Miltonduff 12yo (1980s bottling) – fatty, hints of peat or smoke, tropical fruit, spicy, malty, vanilla

Mosstowie 29yo 1970 (Cadenhead) – fruit, vanilla, buttery, smoky, bitter, warm and mouthcoating, dark chocolate, coffee

So the only whisky which actually got an ‘oily’ note was Glenburgie, one from a traditional still.

The older Miltonduff (again not from Lomond stills) got a ‘fatty’ note and the Mosstowie ‘buttery’.

Not really a strong case for Lomond still whiskies being clearly oilier!

I decided to do another test myself, this time a blind one.

I asked Irma, my girlfriend, to pour for me two sets of three whiskies, in my absence of course. Each set contained, like in the Slainté tasting, whiskies both from Lomond stills and from traditional stills. All I knew was which whiskies were in each set, but not in which of the three numbered glasses they were. The first set contained one Glenburgie and two Glencraig bottlings, so I had to pick out the Glenburgie. Concentrating really on mouthfeel and body, sample (2) was the lightest and cleanest whereas sample (3) was clearly more mouth-coating and, yes, you could call it more oily, than the other two. I decided that (2) was the Glenburgie and it turned out I was right: sample (1) was Glencraig 1970 (Gordon & MacPhail), sample (2) Glenburgie 8 y.o. and sample (3) Glencraig 1981 – 21 y.o. (Cadenhead). Of course, being cask strength, this last sample was diluted down to around 40% for the test. The second set had two Miltonduff bottlings and one Mosstowie bottling and this time I had to distinguish the Mosstowie from the other two. Sample (1) was clearly the lightest, sample (2) was fat and chewy and sample (3) intermediate between (1) and (2). Based on this, sample (2) had to be the Mosstowie. Wrong this time: sample (1) was Miltonduff 10 y.o., sample (2) Miltonduff 1978 – 21 y.o. (Signatory) and sample (3) Mosstowie 1979 (Gordon & MacPhail). Again, sample (2), being cask strength, was diluted down.

In all, this blind test gave an ambiguous result and there is a much stronger link of perceived oiliness with age rather than with still type. So if Lomond still whiskies are not necessarily more oily than whiskies from traditional pot stills, how did the ‘Lomond oil dogma’ become established in whisky literature? My feeling is that, exactly because Lomond still whiskies are basically meant to be variable, some whisky writers just happened to taste a particularly oily Glencraig or Mosstowie bottling. Or perhaps, simply because Glencraig and Mosstowie are often bottled at higher ages than Glenburgie and Miltonduff, they appear to be more oily on average. From those specific tasting notes the general association ‘Lomond = oily’ was born and started having a life of its own.

Only goes to show, yet again, that you should only trust your own palate!

You may wonder why I haven’t talked at all about Loch Lomond and their malt whiskies.

After all, aren’t they using Lomond stills as well? Well, there are several reasons why I focused in this e-pistle on the classical Lomond stills and the malts that were distilled in them. First of all, this e-pistle was specifically looking at the matter of whether or not malts from Lomond stills are oilier than malts from ‘normal’ pot stills. Loch Lomond’s have never been regarded as especially oily the way Glencraig and Mosstowie have been. Second, Loch Lomond uses a pretty complicated set-up of stills and although these stills indeed contain rectifier plates, they are much more sophisticated than the classical Lomond stills. So I regard them not as Lomond stills as such, although they are of course related to some degree. And finally, I am planning to write an e-pistle solely focusing on Loch Lomond’s malts.

Watch this space!

(Published earlier on ‘Celtic Malts’. Thanks to Arthur Motley and the SMWS for information and permission to reproduce their tasting notes; to John Hansell (Malt Advocate) for assistance; and to Paul Dejong and Slainté for making the notes on their comparative tasting available.)