By Olivier Humbrecht, France

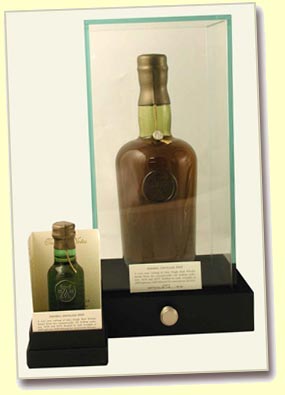

If truth be told, it was the white gloves which tipped me over the edge. The asking price (£2,000 a bottle) is ludicrous of course, but it’s the addition of the white gloves which makes the release of Ardbeg 1965 the most absurdly pretentious idea yet from the half-baked minds of luxury whisky marketeers. Who wears white gloves? The Queen probably, Japanese taxi drivers, oh and snooker referees who, let’s face it, are also used to handling a load of balls. What does Glenmorangie think it is? A perfume company? Oops! Forgot. It is. Ardbeg 65, its price tag, its hand-blown glass made from Islay sand (something even Bruichladdich hasn’t thought of) and the white gloves smacks of LVMH viewing whisky as operating in the same, absurd, fashion as the perfume industry; a place where style will always triumph over content. Adding some seaweed from the shore at Ardbeg would allow you to add another £200 to the price.

If truth be told, it was the white gloves which tipped me over the edge. The asking price (£2,000 a bottle) is ludicrous of course, but it’s the addition of the white gloves which makes the release of Ardbeg 1965 the most absurdly pretentious idea yet from the half-baked minds of luxury whisky marketeers. Who wears white gloves? The Queen probably, Japanese taxi drivers, oh and snooker referees who, let’s face it, are also used to handling a load of balls. What does Glenmorangie think it is? A perfume company? Oops! Forgot. It is. Ardbeg 65, its price tag, its hand-blown glass made from Islay sand (something even Bruichladdich hasn’t thought of) and the white gloves smacks of LVMH viewing whisky as operating in the same, absurd, fashion as the perfume industry; a place where style will always triumph over content. Adding some seaweed from the shore at Ardbeg would allow you to add another £200 to the price.

I’m less concerned about the price simply because I’ve long given up on trying to work out quite how whisky firms work out their prices of their top-end offerings. Asking thousands of pounds for a bottle smacks of… well greed would be the first word to spring to mind. Greed and playing on the desires of deluded numpties who think their lives will not be complete without this bottle. Maybe the 1966 should come with a free box of tissues.

I know what the marketing department’s reaction will be when the price question is raised. “If people don’t think such a rare whisky is worth the money they won’t buy it.” It’s hardly a valid answer. We all know a ‘rare’ official bottling from Ardbeg (or Port Ellen, Brora, Dalmore etc) can demand a stratospheric price because there will always be consumers who are sufficiently obsessive to shell out for it. Top-end whisky is moving in the same direction as top-end wine, a rareified world where the liquid itself is unimportant because most people buy the wines as investments, or fetish objects. In many ways, the price has become the signifier, not the contents of the bottle. The whisky, in other words, has ceased to function in the way in which it was originally intended .. a drink. The super-rich (or deluded, the terms are often inter-changeable) buy these bottles as a trophies. They’ll never drink them. The same applies to whisky collectors.

This upwards shifting in price is all part of malt’s attempts to reposition itself as a luxury product. I have no problem with this in principle. Malt has plenty of luxury cues: scarcity, heritage, the notion of being hand-crafted, the perceived higher quality of the product itself all of which add to the whole experience of drinking the brand.

The luxury market is changing however. It is no longer the preserve of the uber-rich, it is no longer simply about, dare I say it, bling. Luxury has become affordable and as it has, so malt whisky has to justify its price. Although malt isn’t a mass market product (see last issue’s rant) it still needs to be careful not to just slap a high price tag on itself and wait for the consumer to buy into its new position. The collector’s demands and justifications will remain the same. The consumer, however, is changing. They may want luxury, but the brand needs to justify its price, not just with the overall story.. but the taste of the liquid itself.

If malt is to become luxury it needs to engage with the consumer, not withdraw into the esoteric world which Ardbeg 65 is aimed at. The people who buy a Patek Philippe watch will wear that watch, just as if you buy a Rolls-Royce you’ll drive it. Top-end whisky however is in danger of forgetting that its primary function is as a drink.

This isn’t restricted to Ardbeg. This over-inflated sense of worth has driven up the asking price for rare official bottlings (rarely, you may have noticed, independent bottlings!) of Glenfiddich, Balvenie, Dalmore, Bowmore, Glenlivet, Glenfarclas etc etc. The whole industry is playing the same game. In the past couple of years we’ve seen Macallan and Highland Park repositioning themselves as luxury brands by basically repackaging themselves and doubling the price. Is the liquid twice as good as it was before? Of course not. It is the image which has changed.

There is, I would like to believe, a limit to any consumer’s credulity, something which the brand owners should take cognisance of. I once asked Joe Heitz, one of the old school of Napa winemakers, why his wines, so highly regarded, were a fraction of the price of those coming from new producers with no pedigree. “You can cut a man’s hair every fortnight,” he replied, “but you can only scalp him once.” Eventually people will ask the very simple question.. is this worth it? When they do, the liquid better stack up.

Could it happen with malt? Look at Cognac. It too went down the luxury route, with ever more expensive bottles. Then the market those bottles were targeted at (the Far East) collapsed. The result was that the Cognac industry went into a tailspin from which it has only just recovered thanks to American hip-hop community — though even they, the epitome of bling, refused to pay the over-inflated prices for top-end brands. In the interim though, many Cognac houses went bust.

The Cognac industry behaved like a perfume house. It was into packaging, image, elitism, luxury. It had racked its prices up so high that when the question was asked: “is this brandy worth it, do I really want it?”, the answer was “No.” The word which springs to mind is hubris. It’s one that the malt whisky industry could do well to learn.