By Konstantin Grigoriadis, Austria

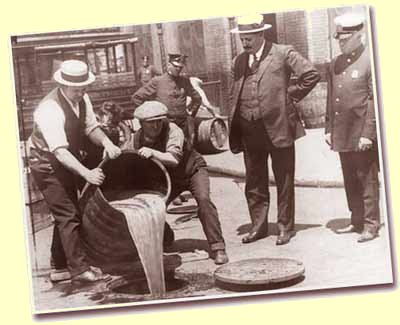

Too much has been written about this period of American history for anything new to be written here. The Prohibition (from 1920 to 1933) led to many violent deaths, corruption and the growth of organized crime on an unprecedented scale. This well-meant policy divided the nation. Prohibition was imposed on a society which neither had the will nor the means to carry it out. Its effects on the whisky industry were profound.

Too much has been written about this period of American history for anything new to be written here. The Prohibition (from 1920 to 1933) led to many violent deaths, corruption and the growth of organized crime on an unprecedented scale. This well-meant policy divided the nation. Prohibition was imposed on a society which neither had the will nor the means to carry it out. Its effects on the whisky industry were profound.

After the restrictions of the First World War, Scotch whisky enjoyed a modest boom, but it proved short-lived as the effects of the Depression began to show. Any hopes of expanding exports to the United States seemed destroyed by Prohibition, and exports of over seven million gallons in 1920 dropped by a million gallons in the following year.

Thanks to a loophole in the American legislation, some Scotch whisky was legitimately imported into the United States for ‘medicinal purposes only’. The quantities of the so imported Scotch were far in excess of the needs as a Medicine, but where far from meeting the demands of the American drinking public. Fake Scotch was being brewed in every available bath or bucket the ‘liquor racket’ (The Liquor Mafia) could get, and unscrupulous German spirit manufacturers added many thousands of cases of their own brew.

The Bottles and Labels where so well made, to appear to be genuine Scotch whisky.

(Faking seems to have a long history…, but the Labels where Beautiful.) The activities of the Fakers suffered a serious setback when Peter Mackie, of White Horse fame, successfully prosecuted one firm for exporting German spirit under the label of Black and White Horse Scotch Whisky. Apart from the whisky which was imported thanks to the medical loophole, the Scotch whisky houses could not legally export to the United States, and most were not prepared to take any direct measures to break American laws. But, if they did not act to meet the demand for Scotch whisky, they knew the American public would either turn to alternatives or have their health and taste for Scotch whisky permanently ruined by the imposters and Fakers.

Records show that exports of Scotch whisky to Canada, the then British West Indies, the French Atlantic islands of St Pierre and Miquelon – indeed to anywhere within reach of the United States – simply exploded overnight. The number of Vessels used for ‘rum running’, (carrying wines and spirits to destinations outside United States territorial waters) was Incredible. It was not quite an safe undertaking, but the dangers where small compared with the risks run by the bootleggers, who were responsible for landing the illicit goods on United States territory and ensuring their safe delivery.

Scotch Whisky prospered under these conditions, particularly as the official distilling of American domestic whiskies had ceased.

However, in addition to the Fake substitutes, the practice of cutting (diluting the genuine Scotch with water, wood alcohol or other eventualy Harmfull stuff) was a further threat. A threat which was successfully turned into an opportunity by Francis Berry of Berry Bros, whose blended whiskies were well established in the United States. Whilst enjoying increased sales, he was very anxious to avoid faking of his whisky. There seemed to be no easy answer, until he met a Captain Bill McCoy at Nassau in the Bahamas, a very popular entrepot for the suppliers of ‘Rum Row’ (the passage in the high seas just outside American limits and stretching 150 miles from Montauk Point on Long Island to Atlantic City in New Jersey).

Berry Bros, a highly respectable firm of London wine and whisky merchants then launched a new brand of Scotch, the first of the ‘light’ whiskies, exclusively for export, the Cutty Sark. For the booming Bahamas market, which was the back door into Prohibition America, Francis Berry saw advantages in working with Captain McCoy, whose reputation for dealing only with genuine goods had led to the idiom: ‘It’s the real McCoy’. (This is just one theorie on the origin of this phrase, in my opinion the most plausible one.

Fact is that it has nothing to do with Dr. McCoy from the 1960’s TV series, Starship Enterprise…)

On this basis the new Cutty Sark established a impressing reputation in the United States which held it until the Prohibition was repealed and after. Chivas Bros, the Aberdeen whisky merchants, were said to be working 24 hours a day to blend and bottle their whisky, which was then packed in waterproof boxes and dropped outside US territorial limits for collection by their ‘customers’. Similarly, Teacher’s supplyied the bootleg trade with Highland Cream in cases sewn up in hessian Fabric.

William Manera Bergius of Teacher’s justified it in the following terms: ‘We are letting the Americans have good Scotch whisky to drink in place of their own somewhat poisonous distillations, and we are bringing good American money into this impoverished country.’

During Prohibition, Teacher’s shipped more than 137.000 cases of Scotch via its own particular ‘rum run’ to Antwerp, and – using a Vessel called Littlehorn- to San Francisco Bay. The owner of Littlehorn was Joseph Hobbs, who was later to become prominent in the Scotch whisky industry. Hobbs, Scottish by birth, spent a great ammount of time in Canada, including a period as a agent for DCL. He returned to Scotland in 1931 when it seemed that Prohibition’s days were numbered and, in preparation for the great boom in the United States market, he entered into association with National Distillers of America to acquire and run a number of malt distilleries, through the Glasgow firm of Train & McIntyre, blenders and merchants.

The distilleries bought were Bruichladdich, Glenury Royal, North Esk (now Glenesk), Fettercairn, Glenlochy, Benromach and the now (sadly) defunct Strathdee Distillery. The Management was given to the Associated Scottish Distilleries Ltd. National Distillers of America withdrew from Scotland in 1954 when they sold Train & Mclntyre and four of their distilleries to DCL.

The American Prohibition was far from being a bad thing for the Scotch whisky industry.

They not only used the time to consolidate its reputation in the United States, but also managed to repel attempts of American distillery concerns to establish themselves in Scotland at this time. But not everything was positive, there were also victims in the Scottish Distillery lansdscape. It is said that Campbeltown whisky boomed during the American Prohibition, but indeed, this period was the cause for many great Scotch brands to loose their reputation. The Big demand for whisky led to a reduction in quality which in turn gave Campbeltown a bad name. During the 1920s all, except for one of the twenty distilleries in and around Campbeltown were closed, the exception being Rieclachan, which closed in 1934. Only two Distilleries returned to active life: Glen Scotia and Springbank.

At the end of the Prohibition in 1933 there was a struggle between American companies for the exclusive agencies for the better known brands of Scotch. Smarter operators had already established themselves, because they undestood that Prohibition was something that would not last long. One of them was Joseph Kennedy, the Boston politician of Irish origin and father of later US President John F. Kennedy. In prospect to the prohibition end, he secured for himself the New England agency for Dewar’s and Haig (as well as Gordon’s gin) and he was importing stocks under special licence for ‘medicinal’ purposes, to be ready for the expected boom after the end of the Prohibition.

It was thanks to the efforts of the import agencies of tha Priod, that Scotch Whisky was able to gain a significant share of the US spirits market, even when something like 20,000 different liquor brands flooded the Market when the Prohibition was repealed.

(Sources: many)