By Doug Fulkerstone, USA

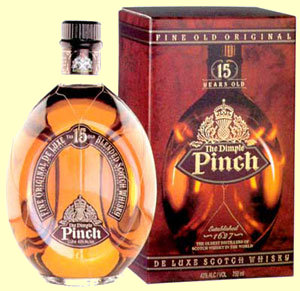

I started drinking whisky in 1978, beginning with a bottle of Pinch (a.k.a. Dimple Haig) that reminded me of fireplace ashes. I was still kind of confused about single malt, vatted malt, blended whisky, aged blended whisky and of course, non-distillery bottlings. As Gordon and Macphail (G&M) were all we could find in Wisconsin back then, along with the usual Glenfiddich, Glenlivet bottles, I started off trying various blends.

I started drinking whisky in 1978, beginning with a bottle of Pinch (a.k.a. Dimple Haig) that reminded me of fireplace ashes. I was still kind of confused about single malt, vatted malt, blended whisky, aged blended whisky and of course, non-distillery bottlings. As Gordon and Macphail (G&M) were all we could find in Wisconsin back then, along with the usual Glenfiddich, Glenlivet bottles, I started off trying various blends.

Ballantine’s 12yo, rather than the 18yo, was great to drink straight (still is.) Dewar’s was kind of bitter and astringent, but White Horse suited my untrained palette, being slightly sweeter and fuller bodied. Grants was a surprise, being mellow and smooth, albeit not particularly memorable (until I discovered the 12 year old, which had a wonderful woody character.)

Picture the vast changes in the 1980’s. Trips to the UK showed how many single malts were available, but very few were here in the midwest (Wisconsin). I wanted to get a taste of each distillery profile, so I began buying distillery bottles first, settling for G&M or Signatory when no single malt versions were otherwise available. What was really funny was, I didn’t realize the sea change that was occurring in the industry right under my nose. Consolidation was the name of the game. What I discovered, however, was that consolidation actually meant: purchase, shut down, then sell the distillery and its contents. Many distilleries were closed permanently, so those are the ones I purchased bottles from first. Then the next big change happened – finishing whiskies in various types of used barrels.

Before 1990, tasters could actually have a decent chance of naming the distillery output in a blind tasting. Once the onslaught, started by Glenmorangie, of various finishes were added to company portfolios, all bets were off. As one writer put it, there was no way in hell anyone could tell whose whisky it was without reading the label. On the other hand, more finishes meant more tastes for more people, leading to a resurgence in single malt purchases. Whisky became a hot item, and with its sudden popularity came the typical price increase. This time, the increases really got out of hand. Single malts that used to be purchased for 20-30 dollars became 50-60 dollars. Esoteric, never before seen single malts (like Rosebank, Ardbeg, Caol Ila, Brora/Clynelish etc.) hit the retailers here, but at a typical $125-250 price tag. The race was on to see who could sell more single malts at higher prices. And of course, once the well-known American affinity for less-strongly flavored drinks (unless they were fruity and sweet) took over, it was vodka that undercut the whisky market, leaving a lot of terrific single malts languishing on the shelves of jump-on-the-whisky bandwagon retailers. In the late 1990’s, you could have picked up some great single malt bargains – if you knew what you were looking at. And let me tell you, the astonishing number of entrepreneurs releasing various alleged whiskies was mind boggling. From no Clynelish in Milwaukee, in one week I found eight various bottlings, all by different “owners” (non distillery sellers.)

And trust me, most of them tasted like turpentine.

So here we are in 2007, and the prices have continued to skyrocket. Auctions seem to be the alternative to winning the lottery, with prices boggling the mind, not to mention common sense. And as with purchasing whiskies that were not aged or bottled by the actual distillery, what you see on the label doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll like what is inside the bottle. Which is not to say I am against entrepreneurs, just that whiskies are quite different, depending on storage, handling, growing seasons for the raw materials and, of course, profiles. It took me 20 years to figure out that a single malt is not from a single cask, but from a single distillery with a minimum age on the label. A ten year old Laphroaig, for example, could have some older Laphroaig mixed in to keep the typical distillery profile. G&M were a terrific example of consistent bottlings- whether I loved the whisky or not, I could count on getting a representative sample of the distillery, even if not the latest distillery kind of profile, from any bottling.

Take Ardbeg, which seemed to change from month to month as it languished in partial production under what was then Allied Distillers, later Allied Domecq. The 1970’s G&M Ardbegs seemed to have a hint of eucalyptus along with the typical briny, peat profile, but when I found a distillery bottling, it turned out to be subdued, with a more Speyside-style body than a muscular Islay taste. Years later, I was told that new make Ardbeg at that time was more like the G&M bottlings than the intermittent distillery ones.

Kind of a shock, eh?

Lately I’ve found myself less and less interested in the new bottles of really old whiskies coming on the American market. I still prefer the 10 year old cask strength Laphroaig (so sue me!) to the 15 or even the 30 year old versions. Why? Because I drink whisky for the taste, and some tastes just really make my taste buds perk up. Which brings me to the really expensive single malts, like the Ardbeg Provenance. First off, let me say it is an amazing whisky. But is it worth $600? Not to me. I’ve found very similar profiles in Glenlivet (1969), Brora (1972), Clynelish (1976), all in the older release categories from the distillery owners. Honest, the same wonderful honey-like, smooth, aromatic, uplifting flavor of the Provenance is matched by, of all things, the Glenlivet 1969. Blindfolded, I would be hard pressed to tell them apart. And that is because they are both from “sugar” casks, aka absolutely amazing single barrels. The same thing happens in American whiskey industry, with various whiskeys from a single barrel standing apart from the rest of the distillery bottlings.

But are these sugar casks representative of the distillery profile? Not to me. They are merely unbelievably delicious one-offs that are fun to try once. For a whisky drinker, they are the equivalent of an aged French grand cru wine, but not something I would drink more than once every few years. The flavor profile just isn’t there. And what I enjoy most about whiskies are their individual characters. Which is why I continue to be bored with all the really old releases, the incredibly high prices and the never-ending list of finishes. For me, if I want a whisky, I want something that will taste of the distillery that made it. I don’t mean each bottle has to taste the same, time after time. The changes in Talisker cured me of that. To quote Jim Murray from 10 years ago, Talisker is a “mean, moody” drink. The old Talisker was strong, iodiney, smoky, peaty and made to be gulped, not savored (at least for my palate.) It was not my idea of a light, summer drink. Then about five years ago, the profile changed. It became drier, more balanced, with hints of smoke, peat, salt along with a firm, full bodied but refined mouth feel. In fact, it at first reminded me of a drier Lagavulin. In many ways, it is a far better-made whisky. But it is still not that “mean, moody” whisky that no other whisky has been able to replace.

I guess with progress comes change.

And with change comes, well, changes…