By Konstantin Grigoriadis, Austria

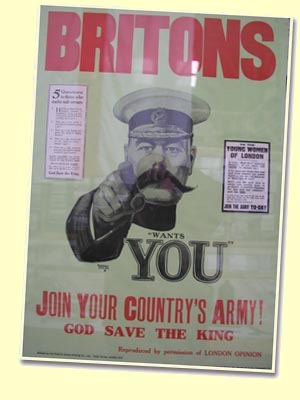

The outbreak of war is always a reason for the introduction of restriction and control. This affects everybody and everything – and the Scotch whisky industry was no exception. The production of Scotch whisky suffered considerably in both World Wars. The restriction was the Intoxicating Liquor Act, which greatly curtailed the licensing hours, followed in 1915 by the Immature Spirits Act, laying down a minimum of two years in bond for all spirits. In the following year, this has been extended to three years.

The outbreak of war is always a reason for the introduction of restriction and control. This affects everybody and everything – and the Scotch whisky industry was no exception. The production of Scotch whisky suffered considerably in both World Wars. The restriction was the Intoxicating Liquor Act, which greatly curtailed the licensing hours, followed in 1915 by the Immature Spirits Act, laying down a minimum of two years in bond for all spirits. In the following year, this has been extended to three years.

The Central Liquor Control Board was set up to control every aspect of the alcoholic drink industry. This was far away from Lloyd George’s dream of nationalising the industry, but the Board had considerable powers and did, in fact, nationalise all of the industry’s activities in an area of fifty square miles around Carlisle, in what is now Cumbria and established the Carlisle and District State Management Board to carry out the day-to-day running of them. A similar arrangement was made for an area around Invergordon. These extraordinary measures were taken because of the large munitions works in these areas and the threat which uncontrolled drinking would pose to safety and productivity.

The Board also decreed that whisky could be sold at an alcoholic strength of 25° under proof (37.2% ABV). By May 1916 the Board had prohibited all distilling except in few cases where distilleries had a license from the Ministry of Munitions for the production of industrial alcohol.

The industry reacted, and a compromise was reached where the pot stills were allowed to continue in production at a level of 70% over the previous five years. A total ban on pot still malt distilling was eventually introduced in June 1917 (not to resume until 1919), while grain whisky distilling continued at a reduced level. The strength at which whisky could be sold was the following: from 1 February 1917 spirits had to be sold within an upper limit of 30° under proof (40% ABV) and a lower limit of 50° under proof (28.6% ABV) anywhere in Britain engaged in the munitions industry. After that sales of whisky on the home market were reduced to 50% of what they had been the previous year.

The problems at home were matched by difficulties abroad, due to the hazardous sea transport, but made worse by the banning of whisky imports in 1917 by Canada and the United States. The final blow came with the 1918 budget which doubled the duty on whisky and imposed fixed prices thus causing the distillers and blenders to absorb some of the increase. Consumption fell drastically and Lloyd George was happy! The grain distillers were in a slightly better position, supplying a Product much needed in the war effort. Although they saw their output fall, and the amount of grain whisky distilled almost cut in half, the emphasis was put on industrial alcohol and baker’s yeast, the latter being a natural side product of the process.

The end of the war did not bring immediate relief, and it was a full year before distilling was free of restrictions.

However, the fixed price remained in force, and the Central Control Board with it, until November 1921. The next twenty years of peace included the closing, in many cases permanently, of a large number of distilleries, the disappearance or absorption of many companies, greater concentration in fewer hands and the arrival of the North Americans on the whisky scene. In 1900 there were over 150 Distilleries working in Scotland, in the Years 1932-33 the number of working Distilleries shrunk to almost 1/10th, to about 15 Distilleries, where none of those was working full time! Nobody was interested to be in the Whisky Business now! The repeal of the Prohibition in the US at the end of 1933 helped, so that a few more Distilleries started a moderate production, with the start of WW2 in September 1939, 92 Distilleries worked during the October 1938 – September 1939 Distilling Season.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, new restrictions were introduced.

There was total prohibition on grain whisky distilling, although the malt distillers, being less dependent on imported raw materials, were allowed to carry on until October 1942 at the latest. A complete ban was then imposed on all distilling until 1944, 45 of the Distilleries where used for drying and storing Grain. The end of the war brought no sign of relief but the distillers had the sympathetic ear of the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, Churchill saw the enormous importance of the Scotch whisky industry and gave instructions accordingly:

“On no account reduce the barley for whisky. This takes years to mature, and is an invaluable export and dollar producer. Having regard to all our other difficulties about exports, it would be most improvident not to preserve this characteristic British element of ascendancy.“

With the coming to power of the Labour government in July 1945 everything changed again.

Their view was that cereals, including barley, must be allocated first to meet essential food requirements.

Supplies to the distillers had to be controlled, and in 1945 were only 43% of the amount, available to them just before the war.

It was not until 1949 that distilling on the pre-war scale was permitted, and the distillers had to wait until 1953, before the rationing of grain supplies was lifted and 1954 for the removal of all the war-time restrictions.