By Davin de Kergommeaux, Canada

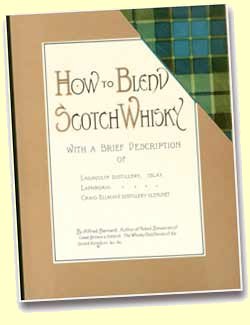

How to Blend Scotch Whisky by Alfred Barnard. 2005; 36 pages (Hanau, Germany)

Schoebert’s Whisky Watch. Originally published: London: Sir Joseph Causton & Sons, pre-1905

When Alfred Barnard, in the employ of Harpers, set out some 120-odd years ago to report on the distilleries of Scotland & Ireland for their Weekly Gazette, he knew relatively little of making whisky, and certainly nothing of what made a good one good. As he proceeded to visit each distillery, his knowledge grew, though as Richard Joynson points out in his introduction to the 2003 edition of Barnard’s better-known The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom, which compiles those Weekly Gazette articles, he never mentions the shapes of the stills he sees onhis journeys, nor makes any mention of cask management.

When Alfred Barnard, in the employ of Harpers, set out some 120-odd years ago to report on the distilleries of Scotland & Ireland for their Weekly Gazette, he knew relatively little of making whisky, and certainly nothing of what made a good one good. As he proceeded to visit each distillery, his knowledge grew, though as Richard Joynson points out in his introduction to the 2003 edition of Barnard’s better-known The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom, which compiles those Weekly Gazette articles, he never mentions the shapes of the stills he sees onhis journeys, nor makes any mention of cask management.

However, Barnard’s weekly appearances in Harper’s during the mid-1880’s lent him widespread credibility so it is not surprising that Mackie and Company, distillers, blenders, and bottlers, would engage him to write an account of their blending facilities and three distilleries. The publication year of How to Blend Scotch Whisky is not known, but presumed to be a couple of decades after Barnard began his whisky journey, and certainly his familiarity with the influence of wood had much progressed.

It is a short book, text filling only 25 of its 36 pages but it is loaded with nuggets, apparently directed at those who blend whisky or buy it in bulk. Judicious use of high quality and well-aged grain whisky is salutary to a blend, but the majority of London merchants, unlike Mackie and Company, used excessive amounts of cheap grain whisky to make inexpensive, barely drinkable concoctions.

Barnard prefers well-aged Lowland malts over grain whiskies for blending and includes a recipe for a most popular blend, which combines 5 parts Glenlivet whiskies, 3 part of Islays, 3 parts Lowland malts, 1 part Campbeltown and only 4 parts, or 25% grain whiskies. “The idea,” Barnard tells the reader, “is to produce a blend so perfect that it strikes the consumer as being one liquid, not many.” Could this be the famous Whitehorse blend developed by Peter Mackie?

Of other techniques, he recommends buying only the finest Highland whiskies for blending, using older whiskies – he suggests an average age of 7 to 10 years as ideal, though accepts from 2 to 4 years old for a public house – and “marrying” blended whiskies by returning them to the source casks for 3 to 6 months after blending. He warns against adulteration of the whisky and suggests that only the softest water, such as that of Glasgow, where, by coincidence, Mackie and Company are located, be used for reducing the whisky to bottle strength.

Barnard ranks age over flavour in selecting blending whiskies, but flavour is second on his list of essentials and among the six classes of whisky – Islay, Glenlivet, North Country, Campbeltown, Lowland Malt and Grain, he ranks Islay the best due to its roundness and fatness. He dismisses an earlier prejudice against Islay indicating “it is [now] more carefully made, the flavour being more delicate and less pungent, owing to the use of dry peats instead of damp ones for drying the malt. Wow! Those less delicate Islays must have been staggering. Islays, by the way, he considers as Highland whiskies.

At Lagavulin Peter Mackie himself escorted Barnard on his tour and Barnard’s description quite exceeds that in his Harper’s rendition, detailing the surroundings, less so the works, but more the processes from selecting barley and making good malt, to careful filling into cask. He compares mashing to making tea and is most impressed with the length of service of many of the staff at Lagavulin. Clearly Lagavulin was Mackie’s premiere distillery and they must have been well pleased with the good light in which Barnard cast it.

Mackie and Company did not own Laphroaig, but were virtually sole agents for their whisky and again, Barnard sings its praises. Things were to change a few years after Barnard’s visit when new owners at Laphroaig terminated Mackie’s agency.

Laphroaig’s output at the time was a mere 24,000 gallons annually and, says Barnard, “the distiller will not increase the size of the plant, nor enlarge the vessels, lest he should in any way alter the character of this highly-prized spirit.” Well, philosophies change and Laphroaig now produces more than 20 times what it did at when Barnard visited.

Peter Mackie founded Craigellachie Distillery in 1888, a year after Barnard completed his tour on behalf of Harper’s, so How to Blend Scotch Whisky adds another distillery to Barnard’s written body of work. Modern whisky pilgrims staying at the Craigellachie Hotel can demonstrate their whisky anorakdom by enquiring in which room Barnard slept while visiting the distillery.

Available at the Museum of Islay Life for 12GBP this unfortunately ISBN-less work provides interesting insights into whisky making of a century ago. Clearly written to promote the business of Mackie and Company, it offers the first-known description of Craigellachie Distillery, along with greater details of Lagavulin and Laphroaig than Barnard’s better-know work. A novelty perhaps, but one from which a novice will gain a good overview of how malt whisky is made while the more experienced malt fan gains new insights into its esoterica.